Written by: Greg Ellifritz

“I like to throw myself passionately into a sport or activity until I reach about an 80 percent efficiency level. To go beyond that requires an obsession and degree of specialization that doesn’t appeal to me. Once I reach that 80 percent level I like to go off and do something totally different.”

– Dan John in Easy Strength

With the arrival of the new year, I’m seeing my gun and combatives oriented friends posting on social media about their new year’s resolutions. Everyone is resolving to do more. More weight lifting. More dry fire. More live fire. More martial arts classes. More running. It’s always more.

Sometimes more is better. But it is impossible to do “more” indefinitely.

Eventually your body will break or you will reach a point of diminishing returns. How do you know when to stop doing more? When are you good enough?

Business author Seth Godin has an answer.

“More might be better for awhile, but sooner or later, it can’t always be better. Diminishing returns are the law, not an exception.

If we look to advertisers, marketers, bosses, doctors, partners and suppliers to tell us when we’ve reached ‘enough’, we’re almost certainly going to get it wrong.

It’s okay to stop when you’re happy.”

What skill level must you have in order to be happy? Have you ever thought about that question?

I think an individual’s ideas about happiness and proficiency change as he or she becomes more knowledgeable and skilled in the subject matter.

One of the problems that causes people to “overdo” their passion is the idea of “beginner’s mind.” To attain mastery in any subject, most people cultivate an intense curiosity and try to examine new ideas and techniques as if they have never seen them before. The deeper one goes in the topic, the more one needs this “beginner’s mind” to stay interested. It leads to the immense appreciation of the tiniest of inconsequential details in the topic of study.

To stay happy, one has to be constantly learning more or improving in some way.

While this attitude allows people to stay interested in a topic far longer than their natural attention span might normally allow, it leads to a problematic and myopic view of the art. It leads to what Jeff Cooper famously called “preoccupation with inconsequential increments.”

By the time one achieves this state, the return on investment is poor. It takes ever more work to get just slightly better. That minor increment of improvement means nothing in comparison to making a more significant improvement in a field of endeavor where you are not as adept.

Basically, at some point in your journey your time will be better spent doing something else.

The cultivation of “beginner’s mind” is touted by hundreds of performance experts. It’s critical for rapid learning, but may have negative consequences long term. Maybe “beginner’s mind” is best left with the beginners.

True mastery of any topic makes one a specialist. Becoming a specialist takes a long period of time. That time requirement is an opportunity cost that will most certainly reduce the time you have available to become adept at other survival skills.

Beyond that, however, there are additional future consequences for attaining true mastery.

What happens when you fail? No one can stay at the very top of the game forever. Challengers and upstarts are constantly clamoring for a shot at the title. Eventually, the “best” gets toppled. At that point, they are no longer “the best.” Can your ego take that hit?

What does it mean to make the mastery of a single topic your life’s purpose when you realize that you are no longer making advancements in the field? At some point in your journey, you will reach a place where you can no longer make measurable improvement. When that happens, how will you feel?

All of that potential pain and anguish is minimized if one seeks adept proficiency rather than absolute mastery.

For me, it is this adept proficiency, not the mastery, that yields the happiness Godin described in the article linked above.

I can shoot well enough to beat 99% of gun owners in a shooting match, but I know I’ll never be the best in the world. It doesn’t bother me that Rob Leatham once beat me in a pistol match. It ultimately won’t bother me when my “Bill Drill” time slips from two seconds to three seconds as my reflexes and muscle strength diminish with old age.

I can still maintain adept proficiency and spend my time building other attributes rather than chasing the glory of a past performance that is no longer physically possible.

If you look at people who are super successful in any field, they get there one of two ways. One way is to be extremely good (top 5%) at a certain endeavor. That takes a massive amount of work and lots of time to maintain. There’s always someone looking to knock you off the pedestal.

Other successful people take a different route. They get very good (top 20%) at something and combine that skill with another skill in which they also have a top 20% rating. Most of these people have three or more skill sets where they are in the top 20% of their field, but no one else in the world has those exact combined skills. It makes those people even more unique than the world’s best performer at a single discipline.

It’s much easier to get to the 80% level and then add another 80% skill to your repertoire than it is to reach the 99% level in a single discipline. It’s a much faster route to excellence than trying to get to be “the best” at any one skill.

Happiness for me equals adept proficiency in multiple fields instead of mastery in one.

Think of it like this:

If you are a top 20% shooter, a top 20% boxer, and a top 20% grappler, you will be in a far better position to defend yourself than the top 5% shooter is without the other skills.

I’ve applied this idea to my life in multiple fields. I don’t want to be Rob Leatham. I want 80% of his pistol skills. Then I want 80% of Louis Awerbuck’s shotgun skills. Then 80% of Phil Singelton’s submachinegun skills. Add 80% of Chris Kyle’s sniping skills.

After that, I want to combine them with top 20% performances in empty hand combatives, knife work, impact weapons work, ground fighting skills, medical training, threat awareness, teaching skills, and writing skills.

That makes my life much deeper than just getting as good as Rob Leatham with a pistol. It’s also more robustly “antifragile.”

I’ve studied martial arts since I was 13 years old. I still don’t have a black belt. Instead, I have high-middle ranking (blue to brown, or about 80%) in five different arts and have a smattering of experience with a whole lot more.

That’s what I’m looking for. I’ll never be a world champion BJJ practicioner, but if I combine decent ground skills, with solid stand up striking skills, a well trained wrestling/clinch game, and some decent kicks, I’ll be a more robust and prepared fighter in general.

This idea that The Future Belongs to the Expert Generalist genuinely resonates with me.

What is an “expert generalist?” The coiner of the term explains:

“Someone who has the ability and curiosity to master and collect expertise in many different disciplines, industries, skills, capabilities, countries, and topics. He or she can then, without necessarily even realizing it, but often by design: Draw on that palette of diverse knowledge to recognize patterns and connect the dots across multiple areas. Drill deep to focus and perfect the thinking.“

– Orit Ganiesh

According to the article linked above:

“The greatest advantage of an expert-generalist, is that he can see connections where others can’t. He develops sort of a sixth-sense and an ability to apply different mental models in a variety of situations.”

Acquiring the “meta skills” described in the article has been my strategy for more than two decades.

Things start coming together. Matt Ridley calls it “idea sex.”

With competencies in broad and varied disciplines, one can’t help but to start seeing connections. Connections that one would never see had he focused on perfection in a single field.

Paul Sharp expresses a similar idea when he says:

“Here is some food for thought. What if you had the verbal agility of a standup comedian, combined with a M/GM rank in USPSA and a Blackbelt in Brazilian JiuJitsu? This is a simplistic example however it gives you an idea of a skill set far superior to any problem we’ll ever encounter. Verbal agility, combined with the physical ability to wreck just about anything you run into? In my opinion, that’s the combo we’re looking for and working diligently towards. Throw in a few more elements and we’re well on our way towards becoming an Adept.”

So, what’s the answer? When are you “good enough?”

The Gestalt approach would be to say “never.”

But that “never” comes with conditions. In any field of endeavor you will reach a point where there are diminishing returns for every hour you continue to study. When you reach that point, I think you should back off that particular skill set. Do enough to maintain your skill level in the discipline, but focus your serious study on another project or idea.

We can never have lifetime continual improvement in any single field. We can, however, get “good enough” at dozens of different skill sets.

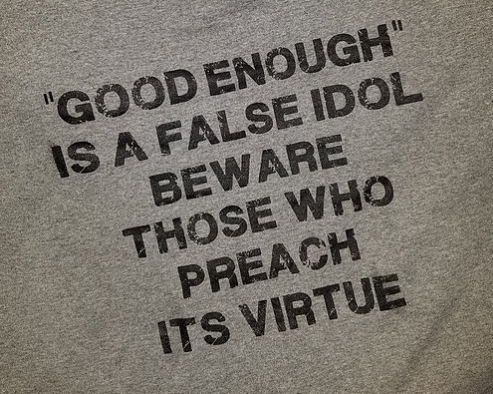

Your whole being should never be “good enough.” You should always be improving some aspect of your life. You can however, be “good enough” in a particular endeavor. When you reach that level of proficiency, it’s time to move on and conquer another skill set.

I hope you all have a wonderful new year.

Some of the above links (from Amazon.com) are affiliate links. If you purchase these items, I get a small percentage of the sale at no extra cost to you.