This story originally appeared in the August 2008 issue.

THE SPRING RUN of white perch up the Potomac has become an obsession with me, a new and improved way to torture myself. The fish are there all right, and success is inevitable given persistence and the right factors: river level, temperature, tide, and luck. After an oh-for-four start, I figured all of this was not likely to come together this season. And then I got lucky. Heidi-Klum-and-me-on-a-desert-island lucky. The-IRS-has-cleared-you-of-any-malfeasance lucky. We’re-out-of-meatloaf-but-can-substitute-the-32-ounce-porterhouse-for-the-same-price lucky.

The tricky thing about luck is that it is often indistinguishable from failure until the last moment. I began that day as I had the others, swinging the boat into the current and dropping downstream, mist lifting off the river just like before. The one difference was that this time I had brought people who actually knew what they were doing: Paula Smith and Dickie Tehaan, experienced perchaholics. I figure if luck messes with you, it’s only right that you should respond in kind.

As we head toward the first of many perch holes Dickie knows from decades of fishing out here, Paula fills me in on the cast of characters around us. The guy anchored midcurrent with four lines out is a union-certified mason who knocks down $37 an hour when he’s working. When the big striped bass are in, he stops working, even though they’re strictly catch-and-release for the next three weeks. He smiles and waves at Paula. He’s wearing his white work duds, right down to the apron, stuffed with bait and tackle. “Guy’s nuts,” she confides, waving back. “Sleeps in his car to save money, then buys fresh lobster tail for bait if nobody’s got herring.” She nods at three guys in a private boat, one of whom razzes her about catching all the fish. “Contractor. Works hard. Good fisherman. Drives two hours here on his day off and goes through a 12-pack before noon. His brother’s worse. He’ll do a case.” All kinds of wackos are subject to the river’s pull. It’s not like any of us three is a poster child for normalcy. Dickie, whose hand-tied bucktails are considered the ultimate perch lure hereabouts, once refused a promotion at work because it would cut into his fishing. Paula, who seldom consumes store-bought protein, is a known eccentric. Me, I’m considered scatterbrained and harmless but accorded a certain grudging respect. Not many at my skill level have the brass to keep showing up.

Dickie is a prospector, checkerboarding the river for fish. He says little, as if clearing the deck of his mind so his hunches don’t have to shout to be heard. Each relocation means I get to pull a 30-pound rock up through 40 or 50 feet of current. So this is how Popeye got those arms.

After two hours, he positions us almost invasively close to where two fat guys have been jigging all morning without a bite. “They’re a hair too tight to shore and too high,” he mutters. I drop the rock, pay out line until I feel it hold. The perch hit our jigs as soon as they reach. bottom. “That’ll work!” shouts Paula, lifting a foot-long fish from the water. Anything over 9 inches is considered good. We hook and release three or four smaller than this for every one we keep. The wire basket tied to the side is nevertheless filling up fast. For once I’m standing smack on the corner of Right Place and Right Time. This is biblical fishing, silver multiplication. The Potomac, insulted by sewage, runoff, and particularly (according to Fletcher’s Boat House regulars) the egg-killing settling agents dumped by the Dalecarlia Water Treatment Plant upstream, can somehow yet deliver an echo of its past abundance.

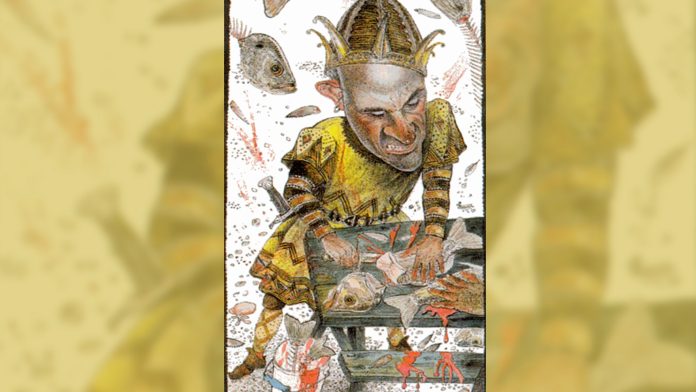

When the fish start flopping free of our overflowing basket, we cut a length of anchor rope for a stringer. Then it dawns on us that we still have to clean all these suckers. I lift the rock one last time. Ashore, we ice the fish and get to work and soon have a picnic table looking like Duncan’s bedroom from Macbeth. The cold fish render our hands slimy, red, and numb, and it seems entirely possible that you could cut yourself, not be aware of it, and keep working until you bleed out and keel over. At which point, we’ve all agreed, the other two can split your share and keep working.

We finish as the sun is setting. I am exhausted but still buzzing with endorphins and vindication. Stick to it long enough and the stars align. I feel like slapping myself for having lost sight of what a gift it is to be alive and jigging. I throw my rod, gear, and fish into the car, light a victory cigar, and roll down all the windows for the drive home. All I have to do now is put my fish in the freezer and get into a hot shower. I park in front of the house, and while closing all four windows, I hear the familiar crunch of a rod tip in a glass guillotine. Today’s victim is of the aristocracy, a top-of-the-line 6-foot 6-inch Fenwick with Aramid Veil hoop-fiber technology that now measures exactly 6 feet. Even this fails to dent my happiness. Breaking a rod, like perch fishing success, is inevitable given persistence and the right factors: electric windows, bumpy roads, a victory cigar. The fact that I was able to get the job done the first time? Just exceptionally good luck.

Read more F&S+ stories.